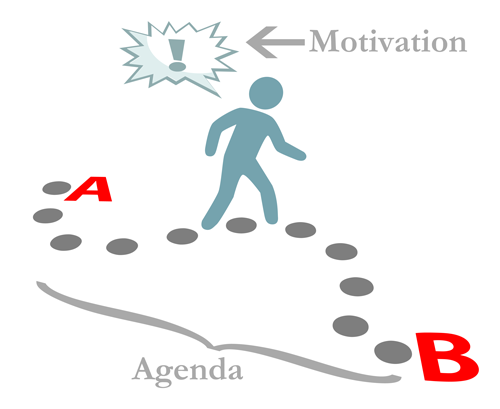

Motivation is what drives characters; agenda is how they get there.

What is the difference between a character who is little more than window dressing for a story and one who is vibrant and realistic? The idea that the character is more than just a plot device, someone who has hopes and dreams and aspirations, however humble they might be. It gives you options for character interactions that are based on more than simple outward appearances.

Major Characters

Here’s to hoping that your major characters already had defined motivations. If nothing else, the plot driver for the story ought to be motivation for the protagonist, and unless you have a shallow or vague antagonist, they should have some strong motivation as well behind their actions.

This is where secondary motivation comes in. Maybe the hero who is off to save the world has debts that need paying. He may get distracted along his righteous path by the lure of easy cash or be considering how to parlay his world-saving into a lucrative venture in the newly-saved world. Your antagonist might be out to rule a kingdom, but maybe he also has an unresolved dispute with another lord that dates back decades and might be even more important to him.

Use these secondary motivations to give an added dimension to a character who otherwise might be monotone.

Secondary Characters

These are your sidekicks, tag-alongs, agents and mentors. There is a good reason for including them in your story. They can provide support and aid for your protagonist or act against him. However, if your protagonist wasn’t around, these people would have other things going on. They have family backgrounds, dreams and aspirations, nagging problems. It’s possible that their goals line up exactly with either the hero or villain but that’s the boring way out. No one wants to read boring characters.

Not having all the actors in your story focused wholeheartedly on the main plot adds a depth of realism. Not everyone is willing or able to drop everything to help out the protagonist. A close friend may have come along out of a sense of duty. A hired mercenary may have dreams of finding the right girl and settling down. A sorceress may have second thoughts about killing the hero after finding out they are distant cousins.

Secondary characters are where the use of motivations and agendas separate from the main plot have the most weight. The hero is expected to focus mainly on the plot (since in many ways he or she is the plot). The depth of the story comes from threads of plot pulling in different directions. Maybe the One Ring would be better used in battle than getting thrown into a volcano. Maybe delivering that princess-saving reward to a certain gangster is a higher priority than helping blow up a moon-sized space station. Neither of these motivations is strictly necessary to the base story but both provide a richness of characterization and obstacles to the hero.

Minor Characters

If you’d like to be obsessive, you can come up with complicated motivations for any character appearing on the page. However, if you’ve done a good job of fleshing out your secondary characters, the truly minor ones probably are best left as window-dressing. Your reader is going to grow weary of getting backstory on every scullery maid and stablehand. If these need flavor, give them distinctive characteristics that are apparent on the surface: appearance, speech, mannerisms. To truly delve into motivations, you need either dialogue or a POV focus on that character, neither of which minor character warrant.

Agendas

To separate a motivation from an agenda basically comes down to planning. A motivation just is. A character is in debt, in love, in trouble. An agenda is a goal that requires work and planning to achieve. If you’re going to get into agendas of secondary characters, be prepared to orchestrate conspiracies, betrayals, and secret dealings. If you’re writing political intrigue at all, this is going to be your bread and butter. Clearly defining your characters’ agendas will help you keep your plots straight and help you plan out the next twist as you see opportunities arise for someone to further their own agenda.

Agendas are important for a writer to understand clearly, since they are a potential minefield of continuity issues. While it’s fine to keep a reader guessing, once they have the pieces put together near the end, they should be able to go back and see an internally-consistent plot (even if poorly executed, we don’t require competence in villains). Do this by setting out in advance what each faction and agent is looking for, who works for whom (actually and officially, in the case that they differ). The better you track all this, the more options you have to produce twists without corrupting your manuscript with logical flaws.

0 Comments